All grief is different, but we can ride the wave together - how we can deal with Covid grief

and live on Freeview channel 276

She had terminal cancer and had bruised herself. Due to the hospital’s restrictions on visitors in effort to prevent Covid-19 spreading, I couldn’t visit her. Eventually, my dad asked me to send her a voice note, since she was too weak to text or call. It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do, recording a message knowing it was goodbye without saying it or getting a response. I never saw her again, and five more people I knew died over the pandemic too.

This story chimes with many of ours, whether we had loved ones die from the virus or other means, our experiences were altered and limited, meaning millions of us around the world are living with grief.

Yet this grief is unique, for many reasons:

- Untimely and unexpected deaths.

- Mass death globally.

- Time of fear from a new virus.

- Restrictions on contact and support.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

- Restrictions on end-of-life traditions like funerals and wakes.

- Lack of stability and certainty.

- Lack of everyday routine.

- Increased loneliness and mental health issues from isolation.

According to the National Library of Medicine, ‘prolonged grief disorder (PGD) cases will rise following the pandemic.’ This was predicted because of the circumstances of death during the pandemic and the pandemic showed similarities to natural disasters which increase PGD prevalence.

Cruse sums up PGD as ‘prolonged grief disorder or complicated grief’ being ‘when intense, long-lasting symptoms of grief, together with ongoing problems and difficulties in coping with life, go on for more than six months after someone dies.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere is no right way to feel after the pandemic, but a study by clinical psychologist George Bonannbo, concluded that almost two thirds of people respond to death with resilience, which means they’re heartbroken but able to function. It’s easy to lose track of how we’re really doing since more or less, things are back to normal, yet the stats tell us that many people needed help over the pandemic for their grief.

SEE ALSO 'You can tell a lot about a person by how they treat hospitality' - My experiences of being a hospitality worker | Death by suicide: What are the signs? How can I reach out? What you can do to help save a life

- Research shows that people bereaved from Covid-19 are experiencing higher levels of grief.

- The total number of people supported by Cruse rose by 52%, those on the helpline by 100%, visits to the website by 37% and social media by 37%.

- The length of calls increased.

- More people approached with complex mental health issues.

- Safeguarding concerns increased.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd the Centre for Academy Primary Care, found in a study that:

- Two thirds experienced social isolation and loneliness after a bereavement.

- Those bereaved from Covid-19 were less likely to be included in care decisions or supported.

- 48% were not provided with information about support.

- 93% had restricted funeral arrangements.

- 81% had limited contact with loved ones.

Unlike a vaccine for the virus, there is no immunisation against grief, so despite the virus broadly being gone, our grief isn’t. Cruse reports that common feelings from the pandemic are shock, trauma, anger, guilt, isolation, and concerns for whether deaths could’ve been prevented. Many people go to GPs with grief as if it is a disease or mental disorder, but Cruse suggests grief is more like being blindfolded in a forest, grief being the forest and the Dual Process Model being getting out of the forest.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

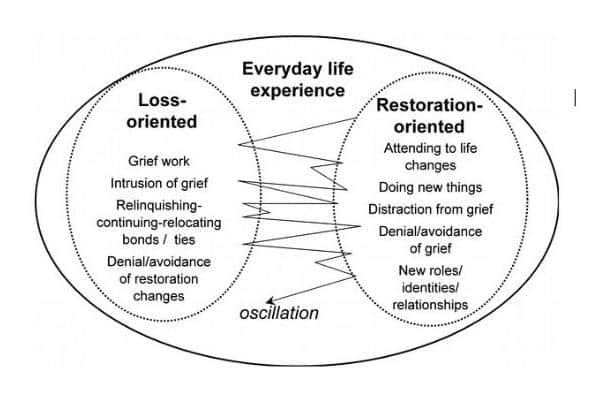

Hide AdThe Dual Process Model sets out a healthy way of grieving that oscillates between loss-oriented thinking and restoration-orientated thinking. For example, saying ‘I can’t believe they’re gone’ to ‘I’m going to raise money for the charity that helped them’.

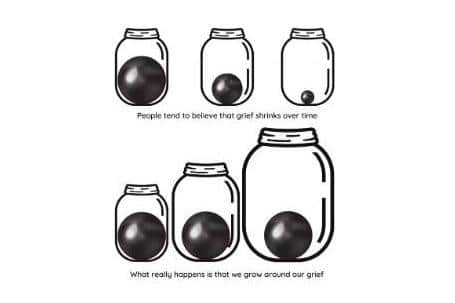

It is when someone is stuck in one way of thinking, being avoidant of their pain, that they tend to get more problems, only asking for help when something is already crumbling and the chances of PGD increase. Many people try to avoid grief, thinking it will diminish over time, when this is what actually happens – (see jar picture).

So, what is crucial then, is that we continue to grow and adapt around our grief. Only recently did I realise that doing something for my mind, body, and soul every day helps me feel more grounded and allows me to keep perspective of my grief.

There are things we can do and acknowledge to help ourselves and others keep growing:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad- Know your normal: sleep, anxiety, energy, irritability, stress, food habits, depression, burnout, fatigue and when something is imbalanced.

- Learn ways to soothe and clear your mind, such as exercise, creative hobbies, helpful friends, reading, mediation.

- It bloody hurts, acknowledge the pain and know you can’t ‘fix it’, but learn to live with it.

- Keep busy but spend needed time alone.

- We must grieve, we can’t pretend or push it down, eventually it will come to the surface.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad- There is no time – frame for grief, no hierarchy pyramid. We want grief to be linear but it’s more like a washing machine of feelings.

Grief is one of the hardest things we endure, and yet one of the least spoken about. When talking about deaths over the pandemic, a volunteer for Cruse said to me that ‘when you know someone is going to die, it’s like looking out to sea, knee deep in sand. When you don’t, it’s like facing the other way and the wave takes you.’ So, free yourself and others by bringing it up, asking questions, and not fearing it. All grief is different, but we can ride the wave together.